A reader of this blog informed me that Walter Lowrie’s translation of Repetition from 1941 contained an essay at the back on all the translations of Kierkegaard into English up to that point. That was actually one of the few older translations of Kierkegaard’s works that I did not have, so I hastily hunted one down on abebooks.com.

A reader of this blog informed me that Walter Lowrie’s translation of Repetition from 1941 contained an essay at the back on all the translations of Kierkegaard into English up to that point. That was actually one of the few older translations of Kierkegaard’s works that I did not have, so I hastily hunted one down on abebooks.com.

The essay is very interesting. There aren’t any revelations in it for people familiar with the older translations, but there is lots of other interesting information. Lowrie recounts, for example, how he was impressed by “the importance the name of Kierkegaard had acquired throughout the Continent, especially in Germany” immediately following WWI (p. 184). I was aware, of course, that the Germans learned of Kierkegaard’s work even while he was still alive, to say nothing of the period after his death. I’d assumed, however, perhaps partly as a result of Georg Brandes’ attempts in the late 1880s to introduce Kierkegaard to Nietzsche, that Kierkegaard’s work was not actually all that well known among German-speaking intellectuals. That is, I’d assumed that if Kierkegaard had become well known in Germany, that, as an intellectual, Nietzsche, would already have been aware of him. When I learned he wasn’t, I like so many other scholars, assumed that Kierkegaard was a marginal figure in German intellectual history.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. “I could hardly pick up a serious book,” Lowrie continues, “without finding his [i.e., Kierkegaard’s] name in it. Every writer who claimed to be abreast of modern thought had something to say about him, and every reputable publisher had to bring out something. S.K. had already taken the place of Nietzsche as the literary vogue in higher circles” (p. 184).

That was revelation to me. Kierkegaard had displaced Nietzsche in early twentieth-century German thought? Of course the popularity of Kierkegaard in Germany in the post WWI period is compatible with his relative obscurity at the end of the nineteenth century. I’m not the only scholar, however, who believed Kierkegaard was a marginal figure in German intellectual history.

It would have been helpful if Lowrie had included some references to specific works. Unfortunately, he didn’t. Fortunately, we have Heiko Schulz’s excellent essay on Kierkegaard’s early reception in the German-speaking world in Kierkegaard’s International Reception, Tome I: Northern and Western Europe. The essay is entitled “Germany and Austria: A Modest Head Start: The German Reception of Kierkegaard.” Schulz appears to have tracked down every reference to Kierkegaard in the last part of the nineteenth century, to say nothing of the early part of the twentieth century, and includes references to specific article titles as well as helpful summaries of their contents. Most of the early German references to Kierkegaard appeared, predictably, in theological journals.

There were early translations as well, Schulz explains however, including Einladung und Ärgernis. Biblische Darstellung und christliche Begriffsbestimmung von Søren Kierkegaard [Invitation and offense. Kierkegaard’s presentation of the Bible and Christian concepts], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold, manuscript (Halberstadt, 1872); Sören Kierkegaard. Eine Verfasser-Existenz eigner Art. Aus seinen Mittheilungen zusammengestellt [Søren Kierkegaard. A unique authorial existence. Compiled from his own communications] trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halberstadt: Frantz, 1873); Aus und über Søren Kierkegaard. Früchte und Blätter [From and about Søren Kierkegaard. Fruits and leaves], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halberstadt: Frantz’sche Buchhandlung, 1874); Zwölf Reden [Twelve discourses], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halle: J. Fricke, 1875); Von den Lilien auf dem Felde und den Vögeln unter dem Himmel. Drei Reden Søren Kierkegaards [The lilies of the field and the birds of the air. Three discourses of Søren Kierkegaard], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halberstadt: H. Meyer, 1876) ; Lessing und die objective Wahrheit. Aus Søren Kierkegaards Schriften [Lessing and objective truth. From Søren Kierkegaard’s writings], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halle: J. Fricke, 1877); Die Lilien auf dem Felde und die Vögel unter dem Himmel. Drei fromme Reden.—Hoherpriester—Zöllner—Sünderin. Drei Beichtreden von Søren Kierkegaard [The lilies of the field and the birds of the air. Three religious discourses—The high priest—The tax collector—The woman who was a sinner], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halle: J. Fricke, 1877); Søren Kierkegaard. Ausgewählt und bevorwortet [Søren Kierkegaard. A selection with prefaces], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Hamburg: Agentur des rauhen Hauses, 1906) (These references are all taken from p. 387 ofSchulz’s essay, though the English translations of the titles are my own).

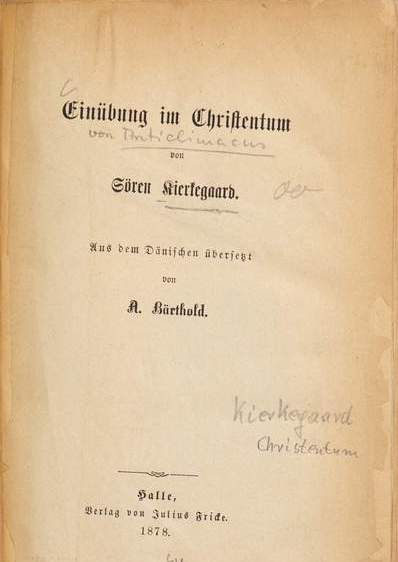

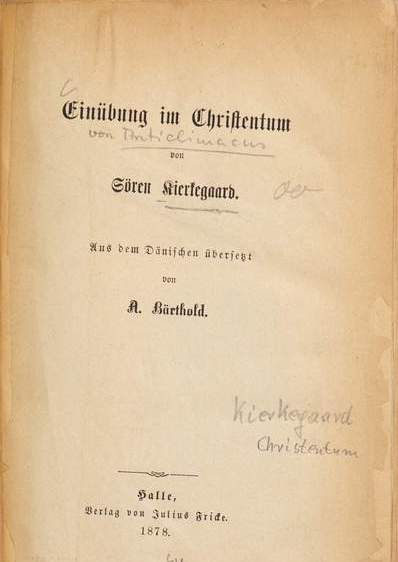

“In addition,” Schulz continues, “Bärthold translated three complete pseudonymous works: Einübung im Christentum [Practice in Christianity], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halle: J. Fricke, 1878); Die Krankheit zum Tode. Eine christliche psychologische Entwicklung zur Erbauung und Erweckung [The sickness unto death. A Christian psychological exposition for edification and awakening], trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Halle: J. Fricke, 1881); Stadien auf dem Lebenswege. Studien von Verschiedenen. Zusammengebracht, zum Druck befördert und hrsg. von Hilarius Buchbinder [Stages on life’s way. Collected, presented to the press, and published by Hilarious Bookbinder]; trans. and ed. by Albert Bärthold (Leipzig: J. Lehmann, 1886) (These references, like those above, are all taken from p. 387 of Schulz’s essay, with the English translations supplied by me).

I’ve always been interested in Kierkegaard’s early reception in Germany because I believe that reception had a strong influence on his reception in the rest of the world. I’ve become more interested in it recently, however, as a result of my interest in George MacDonald. MacDonald’s thought is remarkably similar to Kierkegaard’s. I can find no evidence, however, that MacDonald could read Danish and the earliest English translations of Kierkegaard did not appear until after MacDonald’s death. MacDonald appears to have had an excellent command of German, however, as did most English-speaking intellectuals around the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, and it seems likely that at least some of his reading would have included German theological journals and possibly even early German translations of Kierkegaard. I haven’t had any time yet to research this. That would require tracking down both what books he personally owned, what books and periodicals would have been available to him in the libraries he used, and going through all his correspondence in search of any mention of Kierkegaard’s name.

That said, MacDonald is himself a profoundly original thinker and if his view of human existence and Christianity is remarkably similar to Kierkegaard’s it is not necessarily because he was influenced by Kierkegaard but very possibly because he and Kierkegaard were similar in other ways, and that they understood easily things that the rest of us have to struggle to understand.

A reader of this blog informed me that

A reader of this blog informed me that