Good News and Bad News

A reader, Cassandra Swick, wrote recently to ask me if I could help to clarify a particularly obscure passage in Kierkegaard’s Two Ages. “This passage,” she wrote, “is in the context of his discussion of the present age, where he is pointing out its various deficiencies.

“The Hong translation,” she continued “reads:

The coiled springs of life-relationships, which are what they are only because of qualitatively distinguishing passion, lose their resilience; the qualitative expression of difference between opposites is no longer the law for the relation of inwardness to each other in the relation. Inwardness is lacking, and to that extent the relation does not exist or the relation is an inert cohesion. (p. 78.)

The original reads:

Livs-Forholdenes Springfjædre, der kun i den qvalitativt adskillende Lidenskab ere hvad de ere, taber Elasticiteten; det Forskjelliges Fjernhed fra sit Forskjellige i Qvalitets-Udtrykket er ikke Loven for Inderlighedens Forhold til hinanden i Forholdet. Inderligheden mangler, og Forholdet er forsaavidt ikke til, eller Forholdet er en dvask Cohæsion

That is indeed a difficult passage to translate. The good news is that when you run into a passage such as this, where the new Hongs’ translation is particularly awkward and confusing, you can often get help by locating the same passage in an older English translation. I have an old Harper Torchbook edition of The Present Age and Of the Difference Between a Genius and an Apostle. Sure enough, the passage is there, and in much more lucid prose than the Hongs’. The translation, by Alexander Dru, is a model of the translator’s art. It reads:

The springs of life, which are only what they are because of the qualitative differentiating power of passion, lose their elasticity. The distance separating a thing from its opposite in quality no longer regulates the inward relation of things. All inwardness is lost, and to that extent the relation no longer exists, or else forms a colourless cohesion.

Of course Dru omits “Forholdenes,” or “relationships.” My sense, though, is that Dru’s intuitions were right there, that “relationships” can be omitted without any loss of meaning in that “life” effectively implies “relationships.”

This passage highlights the value of collecting older translations of Kierkegaard, which are still readily available in both brick and mortar used book stores and on Abebooks.com. It also makes clear, a point I have repeatedly made on this blog, that no translation can provide a secure foundation for serious scholarship. I think Dru’s omission of “Forholdenes” doesn’t matter, but I may be wrong about that.

As the title of this post suggests, however, the reason for it is not simply to make clear the value of collecting older translations of Kierkegaard. I also have some bad news for you. This news concerns the searchable online edition of the new Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. My old Bryn Mawr professor, and M.A. thesis advisor George Kline, drilled into me that I must always check the wording of quotations against the original text, so rather than simply cut and past the text of the Danish edition of Two Ages from Cassandra Swick’s email, I went to the online version of SKS to cut and paste it from there.

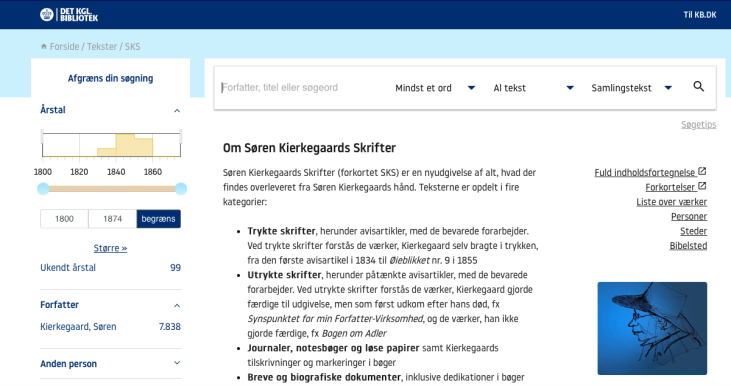

I was surprised to discover that the online version of SKS has been moved from the website of the Søren Kierkegaard Research Center to the website of the Royal Library, a.k.a. Kongelige Bibliotek. The interface is completely different and I had a great deal of difficulty, at first, figuring out how to search the text. The search function across the entire corpus is problematic in that it gets too many false positives. I typed “Livs-Forholdenes Springfjædre” into the search field and got an enormous number of hits that included only “Livs.” I figured that this might have been because I had selected “Mindst et ord,” or “minimally one word” in the search field, so I tried again after I selected “Alle ord” or “all words.” Those results were still problematic, though, in that while the results took me to En literair Anmeldelse, there were still lots of false positives. Only after I went specifically to En literair Anmeldelse and clicked on the link for a PDF of the text, did my search immediately take me to the right passage.

To complicate matters even further, all the search instructions appear to be available only in Danish. It is hard to imagine that they could have made it more difficult for foreigners to search across the whole corpus of the new Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter if that had actually been their objective.