Yet Another Error in the New Kierkegaard’s Journals and Notebooks

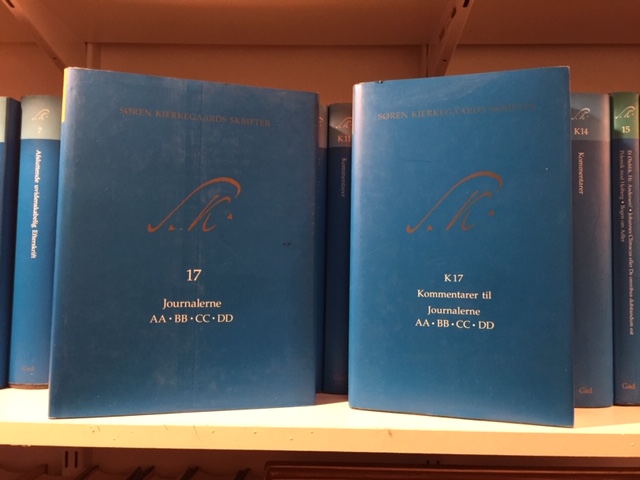

I’ve found yet another significant error in the new Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Notebooks. I don’t go looking for errors, as I believe I’ve explained in earlier posts, I discover them by accident, usually when I’m updating references from the old Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers. Due to the generosity of my friend Sylvia Walsh Perkins, I have a complete set of both KJN and the earlier JP. Most of the journal references in my earlier writing, as well as the notes I’ve made over the years, are to the JP, so when I need to update those references to the new KJN, I go first to the relevant JP entry because that entry always includes a reference to the passage in Søren Kierkegaards Papirer, the only complete edition of Kierkegaard’s journals and papers in Danish. When I find the passage in the Pap. I type the Danish into the searchable edition of the new Danish Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. That then gives me the location of the passage in SKS. The new KJN is keyed to SKS, so once I have the SKS info I can find the passage in the new KJN.

Unfortunately, I keep discovering problems with the new KJN. The problem I am going to talk about in this post concern the following passage from KJN

For a thinker there can be no worse anguish than having to live in suspense while people pile up detail upon detail; it always looks as if the idea, the conclusion, will arrive very soon. If a researcher in the natural sciences does not feel this anguish he must not be a thinker. This is the terrible tantalization of the intellectual! A thinker is, as it were, in hell as long as he has not found certainty of spirit. (KJN 4, 72.)

The Danish for this passage is:

For en Tænker kan der ikke gives nogen rædsommere Qval end at skulde leve hen i den Spænding at medens man opdynger Detail, det bestandig seer ud som kom nu Tanken næste Gang, Conclusionen. Føler Naturforskeren ikke denne Qval saa maa han ikke være Tænker. Dette det Intellectuelles rædsomme Tantalisme! En Tænker er som i Helvede saa længe han ikke har fundet Aandens Vished.

The Hongs render the Danish as:

For a thinker there is no more horrible anguish than to have to live in the tension that while one is heaping up details it continually seems as if the thought, the conclusion, is just about to appear. If the natural scientist does not feel this anguish, he must not be a thinker. This is the most dreadful tantalization of the intellectual! A thinker is literally in hell as long as he has not found certainty of spirit.

Here is how I would translate the passage:

There is no torment more dreadful to a thinker than to have to live in the tension that while one is heaping up details it constantly seems as if the conclusion will come with the next thought. If the natural scientist [Naturforsker] does not feel this anguish, he must not be a thinker. This is the most dreadful tantalization of the intellectual! A thinker is in hell as long as he has not found certainty [Aandens Vished].

The Hongs’ translation of this passage is generally superior to the new KJN translation. There are numerous problems with the translation in KJN. First, the term translated in KJN merely as “worse” (rædsommere) is the same term that is translated later as “terrible” (rædsomme). The latter translation is more accurate in that rædssom has connotations of fear given that it is derived from ræd which Ferrall-Repp translates as “fearful, timid, afraid, frightened, timorous.” One can’t actually call the translation of rædsommere as “worse” a error, though. It just isn’t ideal. The Hongs’ “more horrible” is actually preferable.

The same thing could be said of KJN’s tortured attempt to keep Kierkegaard’s simile “som i Helvede” a simile by translating in as “is, as it were, in hell.” The phrase sounds intolerably pedantic in English, whereas the original Danish, som i Helvede would not sound pedantic to a native Danish speaker. The tone of the original is far better preserved by rendering the simile as a metaphor. That is, som i Helvede is better translated as “is in hell,” without the Hongs’ “literally,” since if some translation of som were necessary, “figuratively” would be more appropriate, but would, again, render a passage that sounds more pedantic in English than it does in Danish.

The last annoying departure from the Hongs’ translation of the passage in question that I’m going to list in this post is the rendering of opdynger Detail as “pile up detail upon detail.” Opdynge, according to Ferrall-Repp means “to heap up, amass, accumulate,” so the Hongs’ “heaping up,” is arguably preferable to KJN’s “pile up,” but again, the new translation does not actually alter the sense of the passage. Even the fact that KJN renders Detail (which has no plural in Danish but which is clearly used in the plural sense in this passage) as “detail upon detail” doesn’t doesn’t actually alter the sense of the passage.

There are lots of these unnecessary deviations from the Hongs’ translations in the new KJN translations. Rendering “Spænding” as “suspense” rather than “tension” is less desirable than the Hongs’ “tension” given that Ferrall-Repp does not list “suspense” as one of the possible English translations of Spænding. Those translations are: “1. tension; 2. estrangement; 3. excitement.” That said, “suspense” isn’t actually misleading. It’s just an unnecessary deviation from the earlier translation. One gets the sense, going through the new KJN, that many of the deviations from the Hongs’ earlier translations were made not because there was any problem with the original, but because the more changes the new translation team could come up with, the greater would be the impression that a new translation was necessary.

No such justification for a new translation of Kierkegaard’s journals and papers was necessary, however, because the Hongs’ translation was not complete. That is, there was definitely a need for a complete English translation of Kierkegaard’s journals and papers. Sadly, KJN is not a complete translation of all of Kierkegaard’s journals and papers because is it based on SKS and SKS is not complete. That is, there’s lots of important material missing from SKS (see earlier posts on the problems with SKS).

The error in the new KJN translation of the above passage is the translation of the Danish man as “people.” Not only is this incorrect, it is seriously misleading. Man, in Danish, just like man in German, is properly translated as “one” (as indeed the Hongs did render it in their translation of this passage). That is, it isn’t other people who Kierkegaard describes as piling up “detail upon detail” (opdynger Detail), but the researcher who is the subject of the passage.

The error in KJN actually gives the passage a different meaning. That is, it makes it look as if the thinker in question experiences rising anxiety, or whatever, as he or she watches other people’s research amass more and more material that would be relevant to some issue to which the thinker is seeking a resolution, or some question to which he or she is seeking an answer. In fact, such a view could be attributed to Kierkegaard, as I in fact did attribute it in the paper I gave at Princeton in July. That is, I pointed out in that paper that science and scholarship, according to Kierkegaard, are collective endeavors, that no individual scholar or scientist can be the sole arbiter of truth in his or her discipline.

The new KJN translation of the passage in question from Kierkegaard’s journals would appear to support such a view and could easily be appropriated by scholars as a reference that would support such a view. The thing is, it doesn’t. It isn’t inconsistent with such a view. It just doesn’t speak to the issue of how the establishment of truth in science and scholarship is a collective endeavor. The issue of this passage is how intellectuals, or scholars and scientists, are actually unwittingly searching for a kind of certitude, or mental calm, that cannot be found in the realm of science and scholarship, or of ideas more generally, but only in the realm of spirit.

So scholars beware. If you are not actually fluent in Danish and have your own edition of Soren Kierkegaards Papirer (or easy access to a library that has it). Then you are going to want to get ahold of a copy of the Hongs’ Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers. As hard as I sometimes am on the Hongs, I think they actually did a very nice job with the journals and papers. Sadly, as I mentioned about, their translation is only a selection, so serious Kierkegaard scholars are going to need to supplement it with references to the Papirer, and that, of course, means they are going to have to learn Danish!

Two of my biggest supporters throughout my career have been the late Robert L. Perkins and Sylvia Walsh Perkins. I met them both at the very first Kierkegaard conference I attended at the College of Wooster, when I was still only a graduate student. One of my professors,

Two of my biggest supporters throughout my career have been the late Robert L. Perkins and Sylvia Walsh Perkins. I met them both at the very first Kierkegaard conference I attended at the College of Wooster, when I was still only a graduate student. One of my professors,