Kierkegaard on Women

As I explained in my most recent post, I chaired a session at the last annual meeting of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association. The session was sponsored by the Søren Kierkegaard Society, so all the papers were on Kierkegaard and they were all excellent. My last post looked at two of the papers. This post will look at the third paper “Gender and the Practical Dimensions of Kierkegaard’s Existential Philosophy,” by the Irish scholar Siobhan Marie Doyle. Doyle’s was one of the best defenses of Kierkegaard against the charge of sexism that I have ever heard. It also raises a very important philosophical question concerning what it means to charge someone with an -ism. What is sexism? What is antisemitism? Are occasional sexist remarks enough to qualify one as “sexist”? The question is equally pressing, of course with respect to the issue of antisemitism. Kierkegaard, as has been well documented by the Danish scholar Peter Tudvad, made some truly horrific remarks about Judaism, but many scholars are reluctant to classify him as antisemitic because there appears to be no foundation in his thought for such a charge. Does a person need to have a world view in which the gender, race, or religion in question figures as deeply flawed, or can genuine prejudice exist alongside an essentially egalitarian world view as a kind of psychological anomaly? These are important questions that deserve more attention than they have been given.

I’m not going to look at those questions now, however. What I want to do now is to summarize for you Doyle’s excellent paper. The paper is divided into two parts. The first part looks at what Doyle keenly observes is Kierkegaard’s “apparent ambivalence toward the feminine throughout the course of his authorship.” Sometimes he praises them and other times he excoriates them. It is indeed hard to figure out what his general view on women is, if, indeed he has one. The second part of the paper looks at Kierkegaard’s “call for the equality of all people, as presented in his ethical work: Works of Love.” Doyle is clearly using “ethical” here in the sense of Kierkegaard’s Christian ethics, rather than the ethical as the state of existence that precedes the religious. Christianity does indeed have its own ethics according to Kierkegaard and Doyle is correct in that it is the ethics of neighbor-love as expressed in Works of Love.

Doyle draws heavily on deliberation II A, B, and C in Works of Love as providing “solid evidence of [Kierkegaard’s] personal belief in the equal status of women and men.”

For Kierkegaard, she writes, “our apparent dissimilarity is merely ‘a cloak’ that disguises our actually similarity.” She then quotes a passage from Works of Love to illustrate this

Take many sheets of paper, write something different on each one; then no one will be like another. But then again take each single sheet; do not let yourself be confused by the diverse inscriptions, hold it up to the light and you will see a common watermark on all of them. In the same way the neighbor is the common watermark, but you see it only by means of eternity’s light when it shines through the dissimilarity (WOL, 89.)

If we are to take this passage seriously, and Kierkegaard clearly meant us to do that, then it becomes very difficult to argue that Kierkegaard considered women as inherently inferior to men, or indeed that he considered people of other races, cultures, or religions, including Judaism, as inherently inferior to white Europeans Christians. Nowhere does Kierkegaard ever suggest that there could be anything about a person that would exclude him or her from the category of “neighbor.” He is a humanist, in the religious sense of that term, through and through because he believed that all human beings were created by God and hence were equally valuable as God’s creations.

So why, then, does he say the terrible things he sometimes says about women? And why does he say the terrible things he sometimes says about Jews? In the first instance, it appears that what Kierkegaard generally takes aim at in his negative remarks about women is more the socially-constructed category of the feminine rather than what one might call the essentially feminine. That doesn’t excuse what he says, of course, but social constructions of gender have been problematic throughout history so it is possible to have a certain sympathy with his occasional attacks on “the feminine” understood that way.

His attacks on Judaism, on the other hand, are harsher and hence more disturbing. They arguably go beyond what would have been considered socially acceptable in 19th-century Denmark. There are negative references to Judaism early in his authorship, but they are relatively mild. His view of Judaism early on appears to have been that, like aesthetic and ethical world views, it was incomplete. His views turn more negative, however, toward the end of his life. Scholars have tended to ignore the virulently antisemitic remarks Kierkegaard made late in life out of a sense, perhaps, that they were anomalous. They certainly do not fit with the beautiful passage Doyle quotes from Works of Love. So where do they come from?

My guess is that they are a product of the persecution Kierkegaard experienced at the hands of the satirical newspaper Corsaren. The attack was initiated by Meïr Aaron Goldschmidt, the editor of Corsaren and a Jewish intellectual for who Kierkegaard had a great deal of respect. The attack has long been thought to have been confined to 1846. Tudvad revealed, however, in his book Kierkegaards København (Kierkegaard’s Copenhagen) that, in fact, the attack extended from 1846 right up until Kierkegaard’s death in 1855! Few people would be able to maintain their psychological equilibrium under such conditions. It appears that that may have been a battle that Kierkegaard lost, finally, in the end.

I examine this issue in more detail in an essay entitled “Kierkegaard: The caricature or the man?” in the January 2020 issue of the Dublin Review of Books. I thought it would be appropriate to draw your attention to this essay in my post on Doyle’s excellent paper because Dublin is her home town!

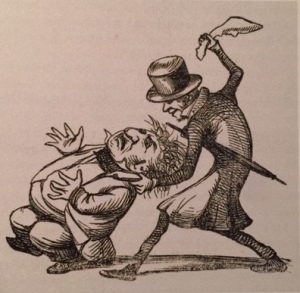

I promised in an earlier post that I would look more closely what scholars refer to as “the Corsair affair,” which is to say the bullying and harassment of Kierkegaard in the pages of the satirical newspaper Corsaren (the corsair) and the effect it had on him. The illustration above is from the February 11, 1848 issue of Corsaren. I have taken this image from Peter Tudvad’s

I promised in an earlier post that I would look more closely what scholars refer to as “the Corsair affair,” which is to say the bullying and harassment of Kierkegaard in the pages of the satirical newspaper Corsaren (the corsair) and the effect it had on him. The illustration above is from the February 11, 1848 issue of Corsaren. I have taken this image from Peter Tudvad’s